Industrial Disaster Response - A Company Alternative.png)

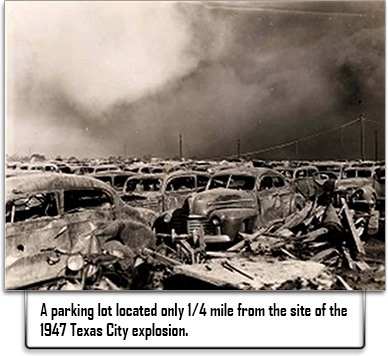

A look at the top ten (1)industrial accidents in US history reveals much that we can learn from. Death tolls, especially from the oldest of the disasters, vary, but all told these industrial accidents have accounted for the loss of from 1508-1558 lives (2). One of those disasters occurred at the Texas City Refinery in Texas City, Texas. On April 16, 1947, a fire broke out aboard the SS Grandcamp, which was loaded with approximately 2,300 tons of ammonium nitrate. The explosion, the resultant damage, and the heat were intense enough that 16 hours later, the SS High Flyer, also carrying ammonium nitrate, exploded violently. There have been many industrial accidents since, but from this one the Refinery Terminal Fire Company (RTFC) was born a year later. At the Ready discussed the RTFC recently with Fire Chief John David Lowe, CFPS. Chief Lowe has worked at RTFC for the past 18.5 years and has been the Chief for about a year.

“RTFC currently has approximately 150 employees, with 130 of those being career firefighters. We operate 7 fire stations throughout Texas and Mississippi, a main communications center, and a training facility,” says Lowe. In addition, the company can serve clients anywhere in the U.S. and Caribbean region. RTFC takes a businesslike approach to emergency response. “Our company operates much as any other traditional business operation, with a Board of Directors, a CEO (Mr. Lonnie Bartlett), a full business staff (Accounting Dept., HR, IT, etc.), and then our operations division that makes up the emergency response and training personnel.”

There are other differences between RTFC and municipal departments and even other industrial response departments. As Chief Lowe explains, “RTFC was designed to be the fire department for the local industry in Corpus Christi, as opposed to other industrial areas that provide for their emergency response needs in-house and then execute ‘mutual aid’ agreements to share resources with other industrial organizations when needed.” As previously discussed in At the Ready, despite their benefits, mutual aid agreements can also be burdensome. Lowe believes the RTFC concept “allows RTFC to respond to all our members’ emergency needs without the normal burdens of legal/insurance complications common when independent companies try to work with each other under a ‘mutual aid’ umbrella.”

A significant number of industrial companies have fire brigades, but RTFC is different from most of these as well. Lowe explains, “RTFC firefighters are ‘career firefighters,’ meaning that emergency response is their sole purpose. We train, respond and think about emergency response 24 hours a day as our only function. Traditionally, in-house fire brigades of individual organizations are made up of existing employees that perform work for their company in some other capacity, such as operating a refining process, and then are given additional training in emergency response on the side.”

RTFC is a full-service fire company that provides industrial firefighting, interior structural firefighting, marine firefighting, emergency medical services, high angle rescue, confined space rescue, trench collapse rescue, hazardous materials mitigation, and incident command and control to client companies. “We also provide emergency response consulting services as well as, inspection/testing/maintenance of safety-related equipment, such as fire extinguishers, fire suppression systems, fire hydrants, fire pumps, sprinkler systems, etc... Additionally, RTFC operates a training facility that provides instruction to firefighters in all disciplines of emergency response,” Lowe says. RTFC firefighters respond to between 650-700 emergencies annually. Lowe explains, “Like most fire departments, medical emergencies account for about 50% of our call volume. Hazardous materials spills, vapor releases, and fires account for another 25% of our responses with the remaining 25% coming from rescues, alarm investigations or other miscellaneous incidents.”

Even with the long history of responding to industrial emergencies, RTFC personnel are always looking to improve. In this drive for perfection, Lowe shares advice for other departments. “RTFC has been responding to industrial emergencies for over 64 years and has developed many of its own tactics, procedures, and practices through its years of experience at actual events. Everything, from the pre-incident planning, to the command and control structures, to strategies and tactics, to the equipment we use, to the way we train our personnel, to the amount of training we provide, to the type of individuals we hire, etc. has been re-worked and revised on a constant basis in an effort to achieve as much perfection as possible. We look at everything—even how we hold a nozzle—in an effort to improve our operation.”

At the Ready asked Chief Lowe what advice he might give to responders to be prepared for industrial emergencies. His answer revealed a philosophy that may be different than other departments, but one that has proven to be successful. “Organizations should plan for their most likely incidents first and then take an inventory of resources and training needed to respond to such an event. Once, this has been accomplished then the focus can be shifted to ‘worst case’ incident planning. Too often I see organizations attempt to tackle the ‘catastrophic incident’ planning first and then spend lots of money and several years trying to gear themselves for the response—all the while the ‘routine’ emergencies are taking a toll on their day-to-day ability to maintain normal operations. Failure to adequately respond to the more ‘routine’ emergencies can often result in an escalation of those events to something much more damaging.”

In addition, Lowe shared more advice geared specifically toward departments that need to establish an industrial emergency response program. “Determine the level of capabilities needed and then set goals, with time frames and strategies, to achieve those capabilities. Having all the necessary equipment and resources, personnel, training, budgets, policies, procedures, and plans in place to successfully and safely operate at an emergency scene can be an enormous undertaking and must be built up over time. Having said that, there is no reason to completely ‘invent’ everything required. The fire service has been around for centuries and has continually evolved into today’s commonly accepted standards and practices. These are all readily available through NFPA and other organizations, and I have found that most professional departments will readily share their own unique insight, procedures, and ‘best practices’ with their peers.”

Industrial accidents are unique, very different from the typical municipal response. Fighting a fire at Mrs. Jones’ house on Elm Street requires fewer personnel, basic equipment, and less time to contain, and she probably did not have tons of ammonium nitrate or toxic chemicals stored in her basement. Industrial firefighting, by its nature, has to be done on a grand scale and presents a myriad of challenges. The typical small or mid-size municipal department has to be prepared for the Mrs. Jones fire and the industrial challenge as well. There are 91 fertilizer plants (3), 144 oil refineries (4), and at least as many chemical plants in the United States.

With these numbers then, and the fact that every emergency is different, the question becomes—is basic equipment enough? Lowe helps to clarify. “It is true that every emergency is different, and most departments would like to be able to overwhelm an incident with their resources rather than merely meeting the minimum resource needed. The vast array of equipment that is available and has a potential for really making a difference in any single and unique event can place a tremendous burden on most departments attempting to acquire all that they may need. Basic must-have equipment would generally be considered to be in the area of water supply (both getting the water – fire pumps, trucks, etc.—and moving it to where it is needed – plenty of hose) and, of course, plenty of trained personnel. Most responders can meet the basic needs, but again if the desire is to be quickly and dominantly successful, a department needs to be equipped to go beyond those basic needs. Therefore, responders need to find ways to supplement their basic equipment, whether that be through a long term purchasing plan, mutual aid agreements with other well-equipped agencies, solid vendor contacts and service agreements, or supplemental plans for additional resource organizations such as RTFC.”

Given the potential for catastrophic consequences resulting from an industrial accident, RTFC offers industry a company alternative and provides career opportunities for firefighters. Industry companies can join RTFC through their website (www.rtfc.org). Chief Lowe explains some of the benefits industry companies who join will receive. “A membership with RTFC allows industrial clients access to professional emergency services 24/7, and most find that such access lowers their overall costs of providing this protection.” Lowe says that overall costs are lowered primarily through lowering of insurance rates, savings from funding “in house” training and equipping of fire brigades, and savings from having additional third party vendors providing required inspection/testing/maintenance services of their existing fixed fire protection systems. When a company joins RTFC, “our staff will meet with potential clients to determine what services they are in need of, visit the facilities requiring service and then develop a ‘risk assessment’ of the client’s facility. An annual membership fee will be developed from this ‘risk assessment’ and presented to the potential client for review.”

1. 1) Texas City Explosion 1947 (550-600 dead),

2) Port Chicago 1944 (320 dead),

3) Piper Alpha 1988 (167 dead),

4) Triangle Shirtwaist Factory 1911 (146 dead),

5) Pemberton Mill Disaster 1860 (145 dead,

6) Grover Shoe Factory Explosion and Fire 1905 (58 dead),

7) Little Rock AFB Titan Missile Silo 1965 (53 dead),

8) Imperial Foods Fire 1991 (25 dead),

9) Phillips Disaster 1989 (23 dead),

10) Boston Molasses Disaster 1919 (21 dead).

2. http://open.salon.com/blog/jrobertg/2009/07/14/weekly_10_the_10_deadlies...

Estimates from Texas City range from 550-600 dead.

3. http://www.tfi.org/sites/default/files/images/usproductionmaps%28updated...

4. http://www.roughneckchronicles.com/Refining/listofoilrefineries.html