By, Dawn Kennedy

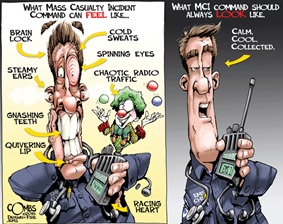

“With great power comes great responsibility.” (Voltaire, popularized by Peter Parker). The Incident Commander (IC) is likened to an orchestra conductor, knowing the instruments, the harmonies, the capabilities of each player. His job is to bring the different sections together for a coordinated response to a public safety nightmare. Unlike a conductor, however, the IC doesn’t typically have all the players organic to his own orchestra. Nope, in the world of Incident Command, each section may be on “loan” through mutual aid, with varying levels of training and experience, while moving around each within a very specialized discipline.

There are no easy answers to this age-old issue. Material solutions exist, but are not universal. Training and experience are variables that have standards, but are not necessarily standardized. Much is demanded of the IC, and blame is easily heaped on the Commander when a Responder is killed in the Line of Duty, and the cause is a perceived failure of the Command and Control system.

A wrongful death claim arising from the Line of Duty Deaths of two Volunteer Firefighters on their first Wildland Call in 1995 was attributed largely to Incident Command and communication failures. Two rookies burned to death in their vehicle. The case is expertly examined in William Nicholson’s 1999 Article form Fire Engineering, “Beating the System to Death, a Case Study in Incident Command and Mutual Aid”.

The role of the IC has evolved over the years since 9/11 because the coordinated efforts of the brave responders to that tragedy was complicated by interoperability challenges, such as; “stove piped” communication channels and departmental codes, separate and distinct command centers by disciplines, and the sheer number of users on the radios. An article by Kelly M. Sharp, with Keri Lovato speaks to the key variables challenging the 9/11 response in Public Safety Communications Magazine.

The Incident Command System mandated by FEMA, the National Incident Management System (NIMS) is not without its limitations, or its critics. A June 2012 article by Cynthia Renaud in Homeland Security Affairs, speaks to the failure of the system to train ICs “to operate on the edge of chaos." For a Law Enforcement examination of NIMS, Chief Thomas Bauer’s Thesis, published by the Naval Post Graduate School, examined “Is NIMS going to get us where we need to be? A law enforcement perspective”

Incident Management Personnel Liability for Injuries/ Fatalities?

NIMS addresses many of the basic challenges highlighted by the research and reports by agencies examining the 9/11 response. The loudest complaints come from an apparent lack of structural flexibility and a failure by the process to address the initial response, by smaller to mid-sized agencies who are on the ground when it first hits the fan. NIMS must be strictly followed, and permits no latitude for the first on scene units to act while, “overcome by events” in the first few minutes of assessment to determine the extent of the true resource response required.

A 2009 Article in Fire Engineering, by New York attorney and Fire Captain Bradly M. Pinsky discussed the adoption of NIMS by agencies as a potential source of liability for lawsuits. The widely cited article explains,

“NIMS is used as a basis for liability because it was an adopted state standard that required no discretion. If an agency is not careful, operating procedures and policies could also serve as standards against which a judge or jury evaluates negligent or reckless conduct.

The law in many states precludes evaluating a first responder’s actions when such actions involve decision making or “judgment calls.” However, some first response agencies have implemented policies under the title Standard Operating Procedures, which give the impression that certain actions are mandatory and not discretionary. Such documents could be introduced into court against the agency to prove that the first responder failed to follow adopted, nondiscretionary procedures.” (emphasis mine). (Also available here)

Recommendations from Captain Pinsky include language that should be used by agencies in their “Best Practices” to lessen the liability of a lawsuit. This of course does not lessen the grief and the tragedy of any LODD, on any scene, anywhere.

Only a month ago, twelve families of the 19 Granite Mountain Hotshots who perished on June 30, 2013 in the Yarnell Fire filed a wrongful death lawsuit, alleging “gross and extreme negligence” and naming the incident commander in the action. (officials: Roy Hall, incident commander for the Arizona State Forestry Division; Russ Shumate, incident commander for the Arizona State Forestry; and Todd Abel of the Central Yavapai Fire District.)

“The complaint alleges that after a lightning strike caused a small fire on a ridge west of Yarnell on June 28, 2013, early efforts to control the fire failed."The Incident Management Team failed to contain the Yarnell Hill fire before the start of the critical burn period beginning at 10 a.m. on Saturday, June 29, 2013," the complaint maintains."

The Command Managers are supposed to simultaneously anticipate needs, direct resources, receive information from “the ground” and manage a multi-agency response across all skill levels and disciplines. This is tremendous responsibility, for every responder on the scene, every victim, every second and third order consequence. Large scale incidents are examined, often for years, with hindsight, weighing decisions against the opportunity to save lives and protect property during the short window of time in which responders have to “stop the hemorrhaging.”

Take a moment this month and look at your “Best Practices”, read the articles linked to this one on reducing liability, check the training for your ICs and personnel, and take a moment to review your relationship with mutual aid agencies. Do you have new personnel? Does your mutual aid partner? Are the comms codes the same? Is there a translation “quick card” in the vehicle? Do your personnel know the procedures, such as “check in?” These self-checks are free. Your personnel are priceless.