by Robert Avsec.png)

.png)

So you want to be an officer in your Fire and EMS department? Before you get started on that path—regardless of whether this will be a promotion on the job or you’re a volunteer firefighter who’ll be selected or elected to the position—I think it’s useful to decide how you’re going to want people to [Fill in the Blank]. For example, will it be:

• An Officer and someone who knows what they’re doing; or

• An Officer and I hope he/she is never leading my crew.

If you ask most firefighters want they want in an officer, you’ll likely get answers such as:

• Knows how to be a firefighter;

• Has situational awareness;

• Can make decisions;

• Treats people fairly; and

• Thinks about others before themselves.

Not a bad list, eh? Certainly a lot more good characteristics are necessary for success as an officer, more than I have space to list in this piece. In the time that we do have today, I’d like to focus on preparing yourself for the task of leading, guiding and directing resources—people, apparatus, and equipment—on the emergency scene. (And even this is going to be a “primer”!)

You can't ever start too early to become a good Incident Commander!

Research into how we make decisions in stressful situations—whether you’re a fire officer or a squad leader in the Army—has shown that we tend to make those decision based upon previous experiences. This phenomenon, known as "R-Prime Recognition" decision-making, holds that when we’re faced with a situation where we need to make a decision, our brain works through an “algorithm” that looks something like this (a very simplistic description):

1. What is the situation? (A kitchen fire in a single-family dwelling)

2. Have I ever encountered kitchen fire in a single-family dwelling? If yes, we tend to execute similar actions to what “worked” the last time.

3. If No, have I encountered or one that closely resembles it (the kitchen fire)? If yes, we tend to execute similar actions to what “worked” the last time.

4. If No, have we encountered such a situation in training? If yes, we tend to execute similar actions to what “worked” in the training situation.

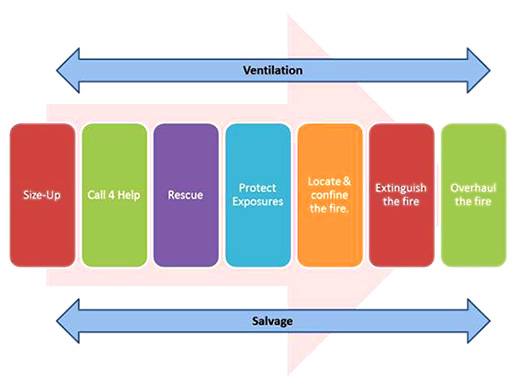

Learn the “7 Fundamental Steps of Firefighting”

In the absence of “R-Prime experience,” you’ll need to know these seven fundamental objectives for fire situation control and use them as your guide for decision-making:

(Salvage and ventilation anywhere these objectives are needed.)

Just like the ABCs of EMS — you can't move to Breathing until you have a secure Airway — we shouldn't move from a higher-priority objective until that primary objective has been accomplished. For example, protect exposures before committing resources to extinguishment.

Learn to Deliver a Good On-Scene Report

This first radio report, usually transmitted from the front seat by the first-arriving officer, should start to "paint the picture" for other responding resources. Those other fire companies should start to "see" the same building and fire conditions as that first-arriving officer.

A standard "On-Scene Report" should include:

• Number of building stories

• Type of construction (Example: wood-frame, ordinary, non-combustible, fire-resistant)

• Type of occupancy (Example: single-family, multi-family, small commercial, strip shopping center, industrial)

• Fire conditions observed (Example: "Fire showing from the second-floor window on "Alpha" side, heavy smoke issuing from eaves")

• Name of the command (Example: Engine 14 has Sand Hills Command).

In addition to the basic information, identify for all companies which side of the structure is Side A for command purposes so that everyone is working from the same "map." Many occupancies these days, especially apartment and office complexes, have really unusual layouts; everyone can have a different opinion regarding which side of the building is Side A depending on their direction of arrival. By orienting everyone to the building layout upfront, the incident commander can avoid communication issues later in the incident.

Continue to paint the picture for those other responding resources with your continuing communication. Include pertinent descriptive terminology such as "garden apartments" or "townhouse apartments" rather than just "multi-family dwelling."

Your on-scene report should sound something like this: "All units from Engine 14. Engine 14 is on location with a two-story, wood-frame, single-family dwelling. I've got fire showing from the second-floor window on Side Alpha and heavy smoke issuing from eaves. Engine 14 has Sand Hills Command on Side Alpha.”

Communicate Incident Action Plan in Size-up Report

Your size-up report — the second radio report after you've left your unit and completed your size-up of the situation — is where you need to articulate what your initial Incident Action Plan (IAP) is going to be. By your articulating the IAP, the other arriving fire companies have a better idea of what tactical objective they might be given.

Your size-up report should include:

• Existing fire conditions ("Fire showing from second-floor window on Charley side")

• Status of incident priorities ("All occupants accounted for, preparing for fire attack with 1¾ line, awaiting rapid-intervention crew before making interior attack")

• Tactical assignments for incoming resources

A good size-up report should sound something like this:

"Sand Hills Command to all units. Fire also showing from second-floor window on Charley side. All occupants accounted for. Operating in offensive mode, preparing for interior fire attack with 1¾ line, awaiting RIC. Engine 1 take RIC and Truck 14 provide forcible entry for fire attack to Engine 14."

Confirmed Communication

Orders received are not orders confirmed until the receiver repeats the message back to the sender. Example: "Truck 3 from Command, forcible entry support for fire attack on Floor 1 with Engine 11.” The order is confirmed when Truck 3's officer communicates, "Command from Truck 3, copy forcible entry support for fire attack on Floor 1 with Engine 11.”

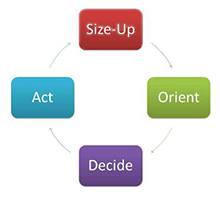

Learn to Use the S-O-D-A “Loop” as a Tactical Leader

The U.S. Air Force uses a mnemonic, O-O-D-A, to teach its firefighter pilots critical decision- making when “in the moment,” e.g., they’re engaged in aerial combat with an enemy aircraft. The O-O-D-A “Loop” stands for:

• Observe: what is the enemy aircraft doing?

• Orient: what are your surroundings, e.g., the terrain, the weather, the performance of your aircraft, etc.?

• Decide: what are your tactical options? Decide on the best option given the present conditions.

• Act: Implement the decided upon option.

The experience of the Air Force is that pilots who become skilled and practiced at working through the O-O-D-A “Loop” more quickly than the enemy pilot are more successful at winning the engagement.

One of my former mentors, Deputy Chief (Ret.) Jim Graham of the Chesterfield Fire & EMS Department, modified this concept for our use in developing the tactical leadership skills of our Company Officers. We called it the S-O-D-A “Loop” and we used it to develop the ability of our company officers to make critical decisions at the “point of attack,” i.e., the location on the incident scene where they and their crew were working:

• Size-Up: Nothing new here, right? Building construction, occupancy type, number of floors, etc.

• Orient: what’s going on in your “little world”? Example: You and your crew are advancing a hose line to a second-floor bedroom fire in a colonial-style, single-family dwelling; you’ve encountered heavy heat and smoke conditions at the top of the stairs that are keeping you from advancing to second floor.

• Decide: what are your tactical options? Continue to advance, possibly into the “teeth” of a flashover? Hold your position on the stairs and call for tactical ventilation of second floor before proceeding? Withdraw completely from the stairwell until the second floor is sufficiently vented? (You’ve got to make one of these decisions, not the Incident Commander. Yes, you have to communicate the action you take to the IC, but only you have all the information necessary to work through the S-O-D-A “Loop” in the limited time available.) Decide on the best option given the present conditions.

• Act: Implement the decided-upon option.

How Do You Learn to Do This?

• Complete National Incident Management System (NIMS) training. As a minimum, a first-line officer should have completed NIMS Levels 100 and 200 from the National Fire Academy (NFA). Even better, get NIMS 300 under your belt as well. All are available on-line in addition to being delivered at locations across the country.

• Complete Incident Management training. NFA offers a wide selection of courses—on campus in Emmitsburg, MD, off-campus at locations around the country, and on-line—to provide opportunities to acquire the knowledge and skills to manage incidents of all types, small and large. Contact the agency that’s responsible for firefighter training in your state, e.g., the State Fire Marshal’s Office, the Department of Fire Programs, the Office of Emergency Preparedness, etc., as many of the NFA classes have now been “handed off” to the training organizations for each state for delivery of those programs.

• Become a student of fire science, Part I. Start by developing your personal library of books that will increase your breadth and depth of understanding of fire, building construction, and strategy and tactics. The foundation of my personal library includes:

• Chief Alan Brunacini (Phoenix Fire Department, Retired). Fire Command: The Essentials Of Local IMS. 2nd Edition;

• Chief Vincent Dunn (FDNY, Retired). Collapse of Burning Buildings: A Guide to Firefighter Safety. 2nd Edition.

• Francis Brannigan. Brannigan's Building Construction for the Fire Service. 4th Edition.

• Become a student of fire science, Part II. Follow fire service bloggers who are writing about firefighting topics on-line. Participate in the discussion. Learn from what others are doing, before you need it. Here are a couple links to get you going:

• Fire Service Warrior

• Fire Officer Mentor

• STATter911.com

• FireRescue1.com

• S.A.F.E. Firefighter

• Traditions Training

• The Company Officer

There is never a better time than the present to begin developing these skills that are critical to the success of an officer as they lead tactical resources on the emergency scene. Whether you’re already a first-line company officer, or someone who desires to be one someday, what are you waiting for? What do you want people to say when they [Fill in the Blank]?